This is part of the Being Pamela series ‘A Tale of Two Snails’ where I write about my recent experiences in the world of ecological art. This series will focus on a course I am currently taking in Art & Ecology with some case studies on my chosen species of interest, the humble snail. I’m hoping to share not just my thoughts on the topics I encounter, but the artistic outputs of these investigations.

Caught Between a Pot and a Hard Shell

This is the story of my reconciliation with snails. I’m an Animal Lover. Capital A. Capital L. I try to find compassion for all living things, even those that creep me out. Like spiders and rats and wasps. Which is why my fraught relationship with snails bothers me. I’m not particularly aesthetically focused. I wear jumpers with paint stains on them and tights with holes in them. My boyfriend had to train me out of wearing odd socks and worse – trying to get away with wearing a Christmas cardigan in July by calling it an Evergreen Tree Cardigan. So I don’t mind the little tell-tale holes that caterpillars, snails and slugs leave in the leaves of my hostas. I even like them a little bit. Like nature’s hole punch has been out crafting through the night.

What I do mind, is when I spend weeks nurturing cosmos from seed only to have their delicate, feathery young leaves consumed whole overnight a mere few days after being moved outside to the garden. I believe in sharing, that my garden is not just for me, but for the love of God would you leave enough of the plant for it to keep living? Everyone, snails included, would be better off. For that reason snails and slugs kind of annoy me. Caterpillars still get away with it because they become butterflies and who doesn’t love a butterfly? Even if you won’t admit it, you do – they’re delightful. Though frankly we do not need them on any more bedlinen, so please branch out thank you very much.

This is how I came to be in a sort of stalemate situation with the snails. I won’t kill them with beer traps or slug pellets (which are also bad for birds and other animals that eat snails and slugs). I occasionally pop them over the wall into the neighbours, but I’ve stopped bothering doing that because it doesn’t seem to impact their numbers even slightly. I try to avoid standing on them. When I do stand on one by mistake I am flooded with guilt and disgust, which sadly happens quite often because the persistent rain of Ireland creates the perfect moist conditions for those slimy fellows. That crunch… It's just awful. I’ve always felt there must be a better way to coexist with the snails, but I just hadn’t found it yet.

So what is Ecological Art Anyway?

It was a sunny day in June. The Summer Solstice of this year. Fifteen of us plus two lecturers Seoidín O’Sullivan and Gareth Kennedy were sitting in a circle in The Field – an ex-carpark, ex-community garden, now overgrown outdoor classroom belonging to NCAD. We were doing an introductory exercise – it was my turn, and I stood in the middle of a circle of people I had just met and introduced myself in the suggested format:

Hi,

I’m Pamela.

I like books and I dislike standing on snails.

That’s how the Art & Ecology certificate with Creative Futures Academy and NCAD began. I had no idea what to expect from a certificate in Art and Ecology. Despite watching the intro video to the course and reading the course description a half dozen times, I couldn’t reconcile how the two subjects would integrate. I could imagine art that was about ecology, but was that ecological art? I posed this question to several creative friends and each said the same thing that had initially occurred to me… drawing?

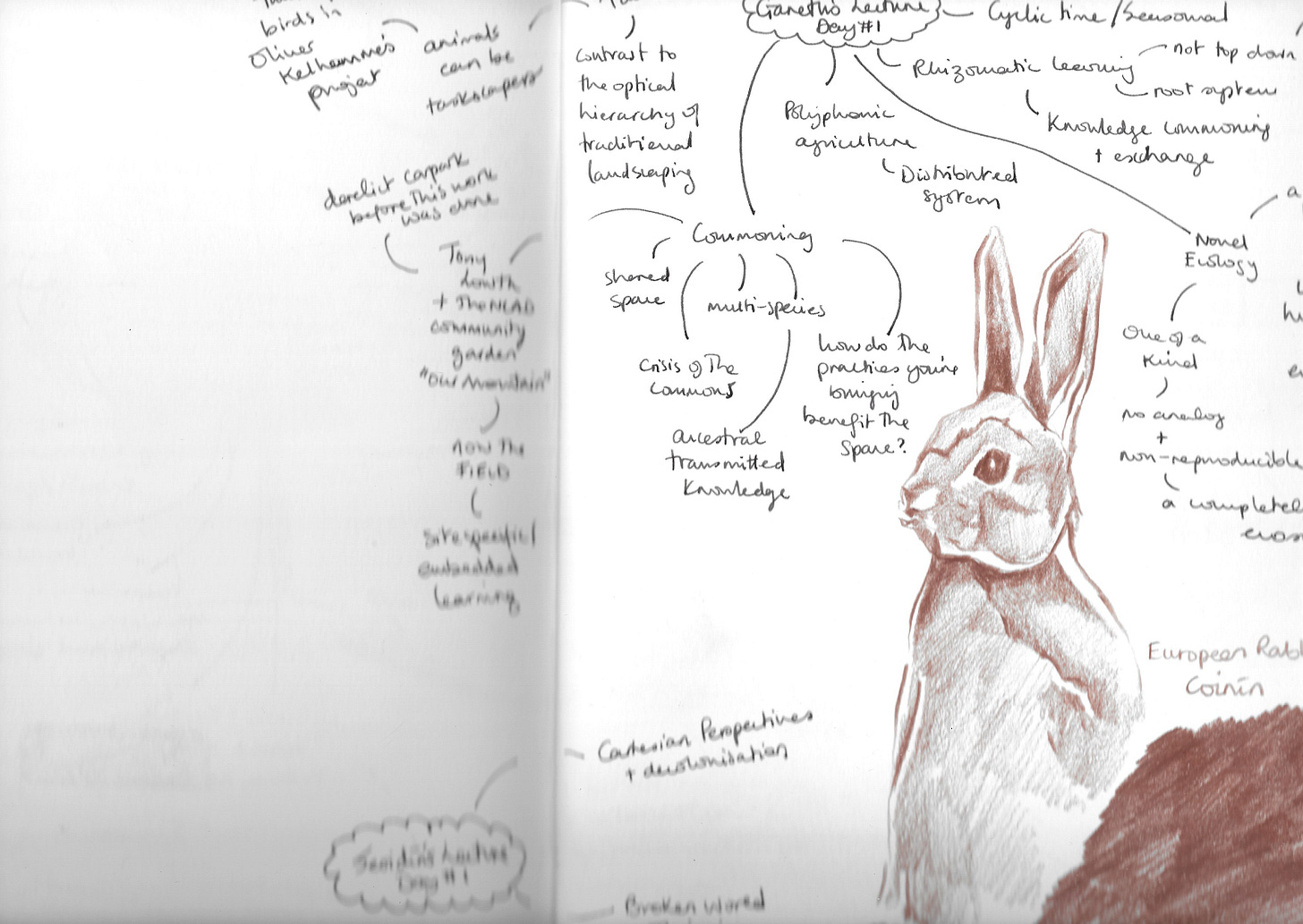

Drawing is how I usually integrate nature into my art practice. The plants and creatures of the natural world making their way into my notebooks – from the reclusive badger to the geometrically perfect artichoke. A little voice in the back of my head insisted that there was going to be more to it than that. Of course there could be drawing. There can always be drawing. Still, I felt there would be trickier concepts to wrangle with and I hoped that the course might offer new challenges as well as a path to a more sustainable practice.

Alongside hands on workshops we explored ideas like the concept of a multi-species future. The imagining of a future that considers all stakeholders from the ant to the oak. This includes humans as much as any other creature. No more, no less. In Courses of Nature Shona McCombes and Lotte van den Eertwegh describe how humans have come to romanticise nature and wilderness. How we separate ourselves from nature by doing so. When we humans are not separate at all. We are organic, living, breathing beings and we are as much part of nature as the bumblebee or the dandelion. This was getting to the heart of what was creating turmoil in my relationship with the snails in the garden. I had all the power, and there was very little except my own conscience to prevent me from using that power to enact a solution that primarily suited my needs and desires, disregarding the needs of the snails for whom my garden was also their home.

This abuse of power only becomes easier the more we abstract away the living of our lives. There’s no better example of it than factory farming. Many of us have become disconnected from how our food and clothing is produced, how our homes are built, how our world works. It is very possible to live an almost entirely digital life now. Have your food delivered to your door. Shop online. Chat on video calls. Seemingly endless sources of entertainment to stream in the form of tv, movies, podcasts and more. We’ve learnt the hard way that it is all too possible to live like this during the pandemic. Except that at least during the pandemic cabin fever and forced social isolation drove many people to take up sea swimming, to discover new walks within 5km of their homes, and to appreciate the free entertainment and beauty of nature right on our doorsteps.

Reconnecting with the material physical world around us with care to the concerns for other beings that we share our immediate space with. Creating opportunities for people to connect with and embrace our own naturalness. And understanding that “urban” environments are still ecologies and ecosystems for not just us but many plants and animals that have come to survive or even thrive in those conditions. Plants like buddleia grow best from rubble. While snails thrive in an environment devoid of their natural predators.

The Trinity Lab Novel Eco gave several presentations during the course and introduced the basic concepts of ecological restoration as well as a newer concept called novel ecologies. Also sometimes referred to as ruderal ecologies, these terms refer to spaces that have been changed by humans but where unique ecosystems have developed in the aftermath of that intervention. Ruderal spaces are often abandoned lots, car parks, or the edges of motorways. The Field is one such place. It can never be restored to what it was before it was a carpark. The space is irrevocably changed. And it would be almost impossible to recreate the Field as it is now. It is home to a completely unique combination of plants and animals.

The Field is in the middle of Dublin 8 and part of what we looked at in the course was the value that such a place can bring to a highly urbanised area like Dublin 8. In our context, as a closed space it was the value as an outdoor classroom and a place to experiment with ideas of how those types of spaces could be used in a community where they were open and accessible to the public. At this point in the course I was all aboard for the environmental aspects of what we were discussing and learning about – but I still wondered, where does the artist come in?

Social Art Practice & Cultural Investigations

I mentioned the upside of having explored local walks and nature during the pandemic. Well not everyone is privileged enough to have green spaces right on their doorstep. Mapping Green Dublin was a project that our course lecturer Seoidín O’Sullivan worked on in collaboration with UCD’s School of Geography and arts organisation Common Ground. The project found that during covid, people who lived in highly urbanised areas, like in the Dublin 8 Liberties area, were largely deprived of green spaces during the lockdowns. Using co-creation and community led approaches the project created an invaluable data set on the number of trees in Dublin 8. Providing local residents with data to back up their perceived experience of the area as a green desert. The project resulted in the creation of a Greening Forum in the area – connecting locals supported by Common Ground with the county council, and resulting in a vehicle for action that has persisted beyond the scope of the project itself.

A social art practice can act as a way of facilitating collaboration and community engagement. In Mapping Green Dublin this took the form of artistic walking and drawing methodologies. Participants were encouraged to engage with their local areas through drawing and mapping. It’s evident the value in this form of artist facilitation as a way to involve all ages and backgrounds in the process.

Then there’s also artists like Oliver Kellhammer who describes his practice as “cultural investigations into the adjacent possible” or, more simply, “botanical interventions”. His work, he says, sits somewhere between commodified art that goes in a gallery and practical interventions that might come from policy makers and specialists in the area of ecological restoration. In his view being an artist allows him a unique opportunity to experiment without the constraints of other fields. In his project collaboration with Janis Bowley entitled Healing the Cut – Bridging the Gap the artists turned what was supposed to be a commission to jazz up a new bridge in Vancouver into one of these botanical interventions.

Kellhammer and Bowley restored a deforested ravine beside the new bridge and created a viewing platform from the bridge itself. They reforested the ravine with willow and cottonwood, enlisting the help of local birds by building bird houses and encouraging the pollinators to make their homes there. An originally green space, turned grey by deforestation is now covered again in green and protected by the intellectual property rights of the artists. This raises the question – if we aim a viewpoint at it, if we view it through a lens or frame, if an artist was involved in its creation, can we call nature itself art?

These two examples were the key ones that stood out to me as illustrative of what ecological art might look like.

Have a thought about anything you’ve read? Share it! Even the tiny ones!

Next time…

Towards the midpoint of the course we were asked to choose a species, plant or animal, that we had encountered at The Field. We were to focus on this species, get to know it, give a short presentation on it and base our final project on it. I was tempted to choose the cute rabbit that had somehow made his home in The Field or the beautiful tall cardoons that were a familiar subject matter for me. I leaned away from those temptations as they represented what I liked, what pleased and delighted me. In the spirit of everything we had learned so far, I chose to focus on the creature I had the most conflicted relationship with – the snail. I’m sure you saw that one coming. Next time, I’ll tell you all about how I came to meet this particular snail at The Field and what I learned about this underrated and mysterious creature.

As always, thanks for reading!

Until next time,

Pamela 🐌

References

Courses of Nature - Shona McCombes and Lotte Van der Eertwegh

Mapping Green Dublin Project Website

Oliver Kellhammer: Healing the Cut - Bridging the Gap

Interview with Oliver Kehllhammer on Future Ecologies Podcast

NovelEco at Trinity College Dublin

You have the ability to take the seemingly least interesting subject and make it engaging! Your drawings, your way of seeing the world and expressing it - all totally unique and magical.

I loved reading this Pamela, got so much out of it.

I feel exactly the same about the power I wield over snails, and even spiders these days. Your course sounds fascinating. And I love the term 'Botanical Intervention'. Also your drawings are wonderful. x